On the outskirts of Moscow on Saturday night, a car bomb claimed the life of Alexander Dugin’s daughter.

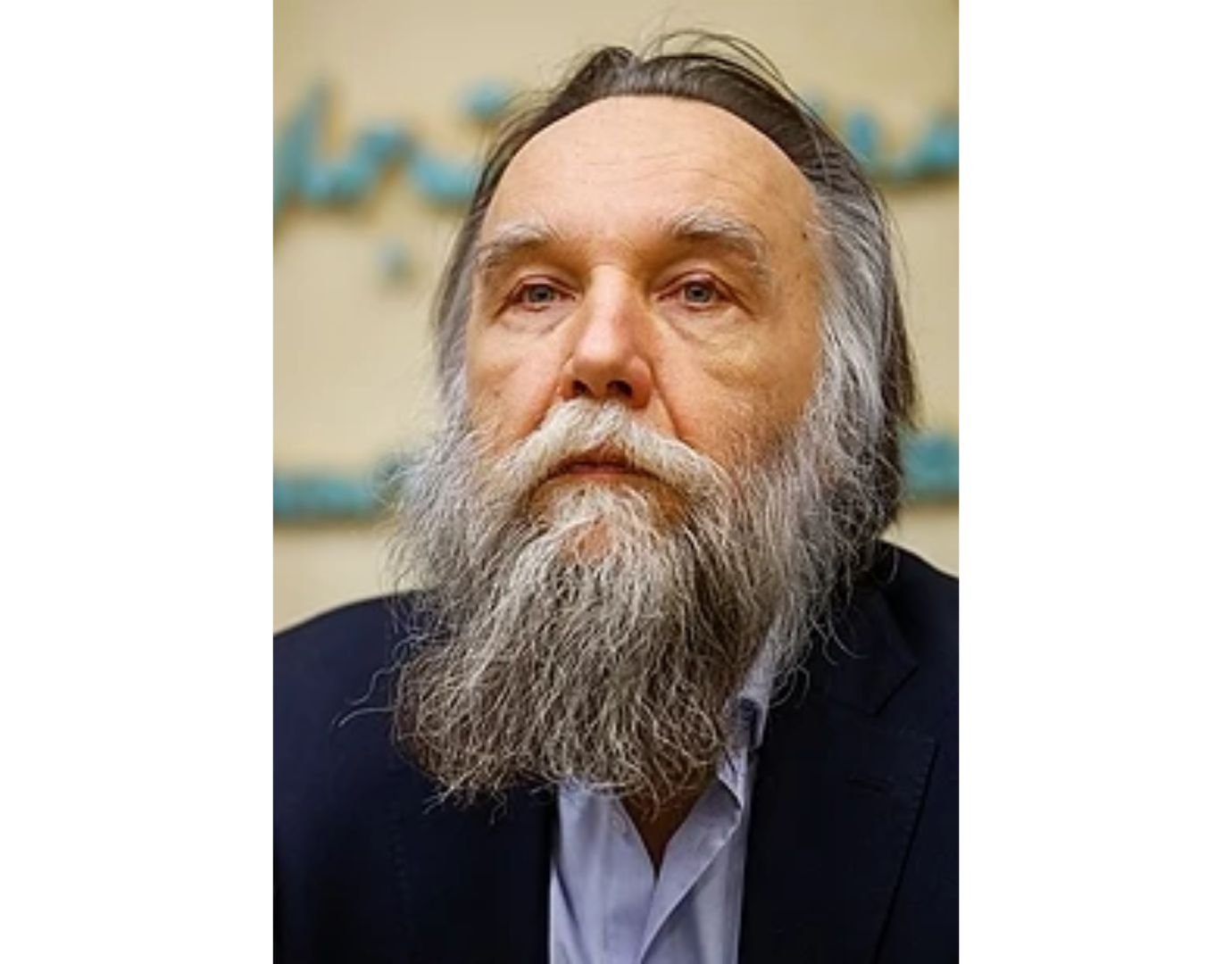

The Russian ideologue Dugin, who has long hair and a white-grey beard, has been referred to as “Putin’s brain” and “Putin’s Rasputin.” Putin’s receptivity to him is hotly contested.

Dugin, who was raised by military parents and was born in 1962, was a young anti-communist dissident. In the final two decades of the Soviet Union, he joined eccentric avant-garde collectives and dabbled in Nazi politics.

He contributed to the far-right Den in the 1990s. In a 1991 Den manifesto, Dugin first described his anti-liberal, ultranationalist vision of Russia. He claimed that the nation would have to contend with the individualistic, materialistic west.

In the turbulent years that followed the fall of the Soviet Union, Dugin and novelist Eduard Limonov co-founded the National Bolshevik party.

Dugin’s 1997 book, The Foundations of Geopolitics, cemented his transformation from dissident to conservative pillar and is now used as a textbook at the Russian general staff academy.

Dugin opposed Ukraine as a sovereign state and urged Russia to regain its influence through alliances and annexations.

He claimed that Ukraine has no geopolitical significance, cultural significance, geographic uniqueness, or ethnic exclusivity.

Eurasia is in grave danger from its territorial aspirations, and continental politics are useless in the absence of a resolution to the Ukrainian crisis.

Putin’s 4,000-word essay, On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians, was widely regarded as serving as the blueprint for the invasion he started six months after it was published.

When Putin was elected president in 2000, Dugin’s anti-Western opinions were by no means commonplace.

While the average Russian embraced western fast food and pop culture, the newly elected leader appeared to be in charge of integrating Russia into the global capitalist system.

Politically speaking, Dugin was irrelevant due to his totalitarian, illiberal ideas. He persisted in writing and lecturing while also creating Eurasianism, a fascist political doctrine with a Russian influence that regards Moscow as a rival empire to the west.

Following widespread anti-government protests, Putin retook power in 2012 and adopted a conservative vision for Russia.

After Kyiv’s pro-Western revolution, Russia annexed Crimea and started a bloody war in the Donbas, and Dugin felt vindicated.

Dugin, one of the most despised Russian public figures in Kyiv, said, “I think we should kill, kill, kill [Ukrainians].”

Dugin kept travelling and kept in touch with New Right thinkers in Europe who opposed liberalism, feminism, and US dominance.

He squared off against Bernard-Henri Lévy in Amsterdam in 2019.

Some have suggested that the assassination attempt on Saturday may have been motivated by Dugin’s vulnerability both inside and outside of Russia.

Dugin is referred to as “Putin’s spiritual guide” by some Russia experts, while others, mostly in Moscow, dismiss him as an irrelevant figure eager to appear close to the Kremlin for selfish reasons. According to reports, Dugin demanded €500 (£425) for media appearances.

Dugin has never worked for the government or been pictured with Putin.

Hours after the bombing, Leonid Volkov, a significant supporter of imprisoned Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny, wrote: “This caricature pseudo-intellectual foist is certainly not part of the decision-making system.”

The political elite in Russia favour his brand of Russian nationalism, which influenced the invasion of Ukraine.

The elite of Russia will be shocked by the murder of journalist Darya Dugin, the father of Dugin.

The burning car will remind people of the turbulent 1990s, when assassinations with car bombs were common. This gloomy era would come to an end under Putin’s presidency.